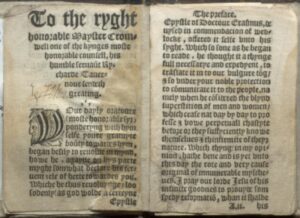

Erasmus, A Ryght frutefull Epystle

Desiderius Erasmus, A Ryght frutefull Epystle, deuysed by the moste excellent clerke Erasmus in laude and prayse of matrimony, London, printed by Robert Redman, 1536. On loan from Blackburn with Darwen Library and Information Service.

1 June 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

When James Dunn gave his collection of rare books to the Blackburn Library in October 1943 just before his death in December of that year, the Northern Daily Telegraph noted that the Library had received ‘the finest gift in its history’.[1] A few months later, the Borough Librarian, James Hindle, noted that Dunn’s gift of ‘rare books…will be of more value to future generations than to our own, and his own notes in the books are of real bibliopolical value’.[2] It is from these hand-written notes that we are able to glean why Dunn considered each book worthy of purchase. In essence, each one of James Dunn’s books had to earn its place in his collection. In his rounded handwriting, Dunn records the merits and interest of each volume at the time of purchase. Sometimes these notes are lengthy and record some of Dunn’s own research on the book in question including some of his own bibliophilic adventures.

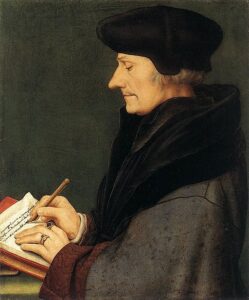

Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam writing, Hans Holbein, 1523. Kunstmuseum Basel Collection.

Dunn’s copy of Erasmus’ A Ryght frutefull Epystle is a rare book indeed, with 16 copies held currently by university libraries in the UK. Dunn records that he knew of only two other copies worldwide when he owned the book. One copy was in the possession of Dunn’s contemporary, A.S.W Rosenbach (1876-1952), the infamous Philadelphian bibliophile, collector and book seller, and the other was in the collection of the British Museum. In his note to his own volume, Dunn states that the Erasmus is the ‘rarest in the collection’. He records his visit to the British Museum where he presented his copy for inspection to one of the librarians. The librarian confirms the rarity of the book, and Dunn notes that it is also observed that his copy was in better condition than that held by the Library. I have not yet compared Dunn’s copy to that held by the British Library, but Dunn’s copy is imperfect, with two signatures wanting. Early printed books produced on handpresses did not print single sheets to make up the pages of a book. Varying numbers of pages per side would be printed on a single sheet depending on the size of book desired. When the sheet was folded it would make up 2 leaves for a ‘folio’ sized book, 4 leaves for a ‘quarto’, 8 leaves for an ‘octavo’ and 12 leaves for a ‘duodecimo’ or ‘twelvemo’. The signature marks were either letters, numbers or sometimes symbols that were printed on the bottom of the first page or leaf of the book’s gatherings to help the printer keep the leaves in order. With two signatures ‘wanting’, Dunn’s Erasmus is missing two sections of the text. Nevertheless, Dunn’s copy may have appeared in better condition than that lamented by the British Library’s librarian. It seems to have been a very satisfied James Dunn who went on his way after this encounter.

The Epystle is a translation into English of Erasmus’s original treatise in Latin. This is a dialogic treatise which proposes new models of Christian conjugal life.

[1]Northern Daily Telegraph, 17th October, 1943

[2]Northern Daily Telegraph, 16th December, 1943