‘A New Meaning in the Roman’ from The Nonesuch Dickens edition of Bleak House, 1937

12 June 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

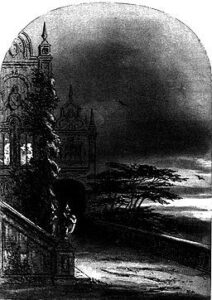

Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), ‘A New Meaning in the Roman’, etching for Charles Dickens, Bleak House, (London: Bradbury and Evans, 1853). On loan from the Harris Museum, Art Gallery and Library.

The anniversary of Dickens’ death on Tuesday of this week has rekindled interest in the murky circumstances of his demise. First proposed by Claire Tomalin in her 2011 biography, Charles Dickens, A Life, is the suggestion that Dickens might have collapsed in the arms of his mistress, Nelly Ternan, while visiting her at the house he rented on her behalf. Tomalin suggests that to avoid a public scandal, the dying Dickens had been secretly transported by Nelly back to Gad’s Hill, where a narrative of the circumstances of his death palatable to his immense public was agreed with the family. This hypothesis is given further endorsement by A.N Wilson, in his new book, The Mystery of Charles Dickens, published earlier this month.

The subject of today’s post, the illustration entitled ‘A New Meaning in the Roman’ comes from Dickens’ novel of 1852-3, Bleak House. It shows the scene of the murder of a central figure in the novel, the lawyer, Mr Tulkinghorn; the keeper of secrets, and the controller of many lives. The Roman of the title is a figure painted on the ceiling above Tulkinghorn’s desk. The figure points silently down at Tulkinghorn’s empty chair, beneath which Tulkinghorn’s body had been discovered, shot through the heart; ‘All eyes look up at the Roman, and all voices murmur, “If only he could tell what he saw!’’’ Modern biographers of Dickens no doubt share this same wish with regard to those who orchestrated his last hours.

Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), ‘The Ghost’s Walk‘, etching for Charles Dickens, Bleak House, 1853.

This illustration is from the original publication of this chapter, ‘Closing in’ of Bleak House. Like most Victorian novels, it was first published in serial form, Bleak House had twenty parts. Each consisted of 32 pages and had 2 ‘plates’ or illustrations, and sold for 1 shilling. The publishers were Bradbury and Evans. The edition we have here is from a much later edition, the Nonesuch Press Dickens published in 1937. The Nonesuch Press Dickens was intended to be the definitive complete works of Dickens, produced by this private press with beautiful paper and a special typeface. What made this complete works publication unique was a controversial inclusion. Along with every complete set of Dickens that was sold, came one of the original engraved steel plates from a first edition of one of the novels. So the engraved plate was used by the Nonesuch Press to produce these editions, and then the plate itself was included with the complete works, packaged in a box that resembled the books with cloth binding and a leather spine. The Nonesuch had 877 plates to dispose of, so the run of the Nonesuch Dickens was restricted to this number.

Bleak House / by Charles Dickens ; with illustrations by H.K. Browne, 1853, London. Held by British Library.

The Private Press Collection of the Harris Museum, which will be discussed in greater detail in the two final weeks of this blog, is very fortunate in possessing not only a complete set of the Nonesuch Dickens, but also one of Hablot Knight Browne’s famous ‘dark plates’ that he produced especially for Bleak House. ‘Phiz’ created 40 etched plates for Bleak House, but for ten of these he used a new technique to produce what he called the ‘dark plates’. The mysterious, misty look of these illustrations was achieved by combining the machine-made lines made by an engraving machine, with lines made by hand with an etching needle. The dark plates could be simultaneously detailed and suggestively atmospheric. In what was also very pleasing to Browne was the fact that the merged techniques of the dark plates were very difficult for forgers to copy.