Barbouyo, Rosa Bonheur, (1822-1899), Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery

13 August 2020

By Catherine McManus, Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery Apprentice

Rosa Bonheur was born in Bordeaux, France in 1822. Moving to Paris with her family when she was six years old, Bonheur’s troublesome behaviour resulted in her regularly being expelled from school, until her father—landscape and portrait painter Raymond Bonheur—intervened to begin formally training her as an artist. Renowned for her advanced style of realism, Bonheur first exhibited her work at the age of nineteen in the Paris Salon, at a time when women were often excluded from the art profession based on their gender.

‘Barbouyo’ provides an example of the skilled style of realism Rosa Bonheur was capable of after studying the anatomy and osteology of animals in abattoirs or in the École nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort in Paris. Attaining official police permission to wear men’s clothing as a way to move through public spaces without drawing attention, Bonheur would attend horse markets twice weekly, sketching and studying their movements for her innovative work, The Horse Fair (1852–55; The National Gallery). Her habits of chain-smoking and wearing trousers were certainly unusual for the time-period, but these habits enabled her to move with a greater freedom in the restrictive atmosphere of the 19th century.

The Horse Fair, Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) and Nathalie Micas (c.1824–1889) (possibly), The National Gallery, London https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-horse-fair-115640/

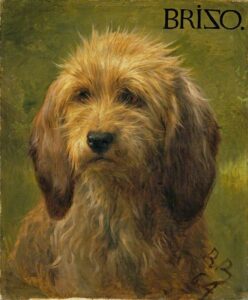

Brizo, A Shepherd’s Dog, Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) The Wallace Collection https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/brizo-a-shepherds-dog-209383

Finished in 1879, ‘Barbouyo’ is a similar piece to Bonheur’s earlier depiction of an otterhound painted entitled Brizo, A Shepherd’s Dog. Bequeathed to the Wallace Collection in London by Lady Wallace in 1897, Bonheur’s menagerie of animals extended into the realms of the bizarre with her ownership of cattle, otters and even lions.

Living alongside her companion and partner Nathalie Micas for over forty years, after Nathalie’s death in 1889, Bonheur went on to form a relationship with American painter Anna Klumpke lasting for the rest of her life. Buried alongside both women at the Père Lachaise cemetery in 1899, the shared headstone reads ‘Friendship is divine affection’. As a queer icon comparable to the likes of figures such as Anne Lister, Bonheur could potentially be characterised as the French “Gentleman Jack” in the sense of her dress, lifestyle and mannerisms.

As more research into historically marginalised figures comes to light, revisiting and reinterpreting museum collections allows for the lives of pioneering individuals such as Rosa Bonheur to be celebrated for their differences and struggles in a way which, in life, they seldom found the opportunity.