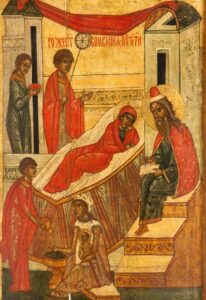

1. Icon of The Birth of John the Baptist, Novgorod, ca 1500, Strang Loan, Blackburn Museum

9 June 2020

By Mike Millward, former Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery Manager and Curator

Icon is a Greek word meaning “image.” Today it is more likely to suggest a digital pictorial shortcut on a phone or computer screen or a famous celebrity or building (“football icon Lionel Messi” or “the iconic St Paul’s Cathedral”) than a portable image painted on wood and venerated by Orthodox (Eastern) Christians, which is what I am writing about here. They are the most numerous holy artefacts of Orthodoxy and have great significance to Orthodox Christians.

There are literally millions of icons, and they are still being produced in great numbers today. The greatest number are Russian; as the one great Orthodox country not subject to the Ottoman Empire, Russia became the centre of the Eastern Church during the 15th century. Like almost all Byzantine and Russian art before 18th century, the subject matter of Icons is religious: The Virgin and Christ, Saints, Biblical figures and events from Christianity.

Russia had been a threat to Constantinople since the 9th century, but in 988 Vladimir I Prince of Kiev married Anna, daughter of Byzantine Emperor Basil II. He was baptised, and converted his subjects in a defining moment of Russian history. After Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453, Russia as the one free Orthodox country, saw itself as its successor and even as the Third Rome, with the Tsar as God’s anointed, so that the contemporary Ivan IV (“The Terrible”) could compare himself to a Byzantine Emperor. The later history of Russian Orthodoxy was not without difficulties, but the Church remained strong and even survived the Revolution to become prominent again after the Soviet collapse. More icons from Russia survive than from any other source because of its size and long continuous history.

One striking feature distinguishing icons from western religious art is their lack of interest in innovation. Not concerned with depicting space or movement, the icon painter’s role is to show the spiritual world beyond earthly reality. Since the Renaissance, western art has been obsessed with novelty and progress, whereas Orthodox art is concerned with tradition and validity. Icons often disappoint modern western eyes, appearing static, unadventurous, repetitive and primitive. Their qualities of constancy and permanence are simply not of interest to western observers.

The most highly venerated icons are often in poor condition, over-painted many times. This is because icons are not primarily viewed by believers as “art.” Spirituality is far more important than realism. A copy of a powerful icon can inherit its power, hence the proliferation of copies of so-called “wonder-working” icons throughout the Orthodox world. Hundreds or thousands of similar images turn up over many centuries. They are almost never signed or dated making it almost impossible to identify schools or periods. Composition is not subject to whim, and ideally a copy of an icon would be undisguisable from the original. Despite this, development inevitably took place over time and was subject to influences and place.

Stylistic differences between the religious art of East and West also include the use of perspective, space and anecdotal detail. Very strange to us is the “reverse perspective” in which the vanishing point is in “real” space occupied by the observer. Traditionally, all activities in icons are shown taking place outside, but we know it is actually inside by the device of a cloth draped over the buildings. Both these devices are clearly visible in the Nativity of John the Baptist above. Icons generally lack anecdotal detail, removing one of western art’s principal means of introducing variety into paintings on the same theme.

2. Iconostasis in the Church of The Dormition of the Holy Mother of God, Varna, Bulgaria, 1602

Orthodox worshippers connect directly with icons. A few minutes spent in an Orthodox church will generally be enough to see worshippers stopping to venerate particular icons, often kissing them. Such daily use can result in icons being in poor condition. Sometimes this can be rectified by cleaning, sometimes not (with minor paintings, the cost of conservation can be considerably higher than an item’s monetary value). Icons were often over-painted when their condition deteriorated to the point of being difficult to see properly, resulting in old and famous icons having multiple layers of repainting over dirty ones beneath, creating serious conservation problems. Alternatively, old icons might be scraped clean for re-use rather than thrown away.

3. Diagram of a large Russian Iconostasis (Icon screen)

All this can lead to great difficulty in identifying the date and identity of icons – in contrast to western art, where style and technique are important aids to identifying and dating works.

Icons can be found in private homes singly or as part of a shrine, and in churches, individually displayed, for example on a desk or on a wall, or as part of a screen.

The icon screen or Iconostasis (Fig 2 & 3) is a prominent feature of the display of icons in Orthodox churches. If you have been into a church in Greece or Bulgaria while on holiday you are likely to have come across one, but it developed to its greatest heights in Russia, reaching extraordinary size and elaboration.

The Iconostasis developed gradually during the later Middle Ages as icons were displayed on and around the enclosed area reserved for the priest. The formal arrangement varies from country to country and church to church, but more or less standard features occur widely. The diagram shows the arrangement of a large Russian Iconostasis with many elements present. Smaller screens had fewer icons and less variety. For example, the lovely screen in the Bulgarian Church in Fig 2 has only two main rows of icons.

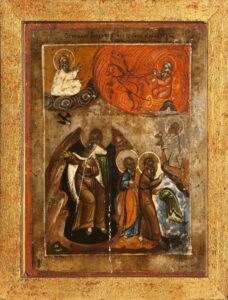

4. Scenes from the Life of Elijah early 19 century

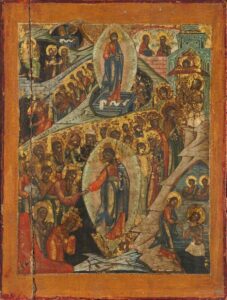

5. Anastasis, Russia, 18/19 century

Most of the icons at Blackburn are small, and were probably personal items used in peoples’ homes. Icons in screens are often, though not always, larger and more imposing. The icon of The Forefather Abel in my post about how the icons came to Blackburn, would most likely have come from the top row of a large screen, where Abel would have been amongst the Patriarchs (See the diagram). The row below holds the Prophets, such as Elijah (Fig 4). The Liturgical Feasts, the major events in the life of Christ and Mary, His Mother, include the Resurrection. The Orthodox view of this event, or Anastasis, shows Christ’s descent into Hell before ascending to Heaven (Fig 5).

6. Deesis with Saints, Russia, early 18 century

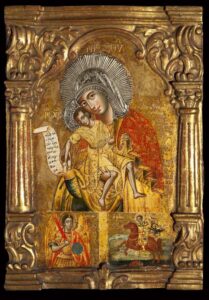

7. The Kykko Mother of God, Greece, early 19 century

The Deesis in the diagram is a row of large icons with Christ in the centre, Mary and St John on either side and behind them many of the major Saints interceding with Christ on our behalf. Deesis is also represented in small icons such as Fig 6 from the Blackburn Collection.

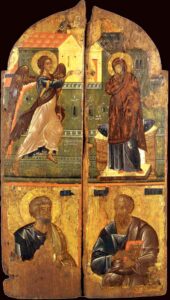

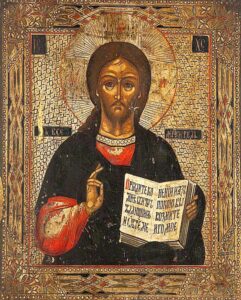

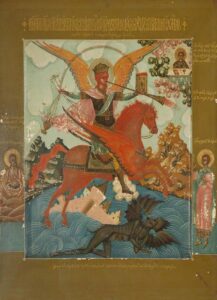

On the ground floor level of the screen are the Royal Doors, through which the Priest can access the altar. Above the Doors is often a Last Supper, and on the doors themselves, a representation of the Annunciation and some or all of the Evangelists, or other Elders of the Church (Fig 8). On either side are Mary, the Mother of God (Fig 7) and Christ (Fig 9) or sometimes the Saint to whom the church is dedicated. Beyond them are the Archangels (Fig 10).

8. Royal Doors, 16 century, Nessebar Archaeological Museum, Bulgaria

9. Christ Vsederzhitel, Russia, 18 century

10. The Archangel Michael, Russia, Palekh School, c.1800

This brief description of the icons in the Iconostasis cannot convey their variety and complexity. I will attempt to deal will some individual icons in more detail in future.