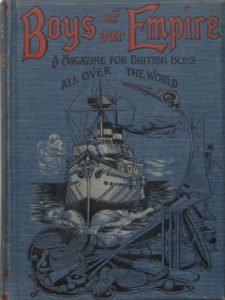

Boys of Our Empire, an illustrated magazine for boys all over the world, vol. 2, 1902

Boys of Our Empire, an illustrated magazine for boys all over the world, vol 2, (2nd November 1901–27th September 1902), edited by Howard H. Spicer (London: Andrew Melrose). Loaned by the Harris Museum, Art Gallery and Library. Image © Harris Library, Preston.

Wednesday 8 April 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

The Education Act of 1870, along with a sense of rising prosperity and technological advances in printing both text and images, combined to produce the conditions for the birth of a new publishing phenomenon during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Books written specifically for the youth market, both fiction and non-fiction, and children’s periodicals; inexpensive magazines aimed specifically at young readers, became a publishing sensation. Both the rise in literacy, and the increasing amount of leisure time enjoyed particularly by the middle classes, created cultural conditions perfectly poised for the reception of this new publishing trend.

Henry Spencer’s collection of children’s literature is particularly rich in its holdings of late Victorian and Edwardian periodicals and annuals for both boys and girls. The theme of the British Empire and that of Christian values represent two dominant strands in this literature. Union Jack: a magazine of healthy, stirring tales of adventure by land and sea for boys (edited by our previously featured author, George A. Henty), represents this trend. In contrast, the publications of the Religious Tract Society and other religiously motivated concerns sought to combat the influence of a third strand of the periodicals, the penny dreadfuls. Dawn of Day (a monthly published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge) is a typical example of this genre. The disreputable penny dreadfuls included more lurid material such as murders and robberies, and also recounted tales of cheeky, sometimes anarchic figures, like Jack Harkaway. These characters’ victories were for themselves, as opposed to the Empire, or for Christian salvation. Spencer’s collection contains no examples of the penny dreadfuls in magazine format, and only 8 in serial form as opposed to 102 examples of periodicals which focused on Empire or salvation. Spencer’s chapbooks reveal more examples of the penny dreadful subjects. We will examine these in future posts.

The example here, Boys of Our Empire, was a short-lived publication, active only between 1900-1903. It has been described as ‘the most jingoistic of all the juvenile periodicals’ (Patrick Dunae, 1980), and it is associated with the formation of the British Empire League or the Boys Brigade, designed to inspire patriotism and ‘Christian manliness’. While tales of adventure are the dominant trope, an interest in the commercial activities of the British Empire is also discernible, and it is worth remembering that many such as G.A. Henty, and Arthur Conan Doyle, a contributor to Boys of Our Empire, held shares in companies profiting from British colonies.

Next time: John Henry Spencer Children’s Collection continued.