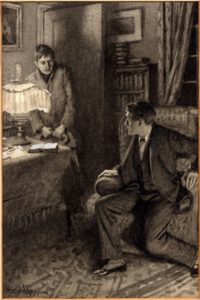

‘The Brothers’, Harold Copping

Harold Copping (1863-1932), The Brothers, watercolour, ink, gouache on card. Loaned by Towneley Hall Museum and Art Gallery. © Towneley Hall

28 April 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

Harold Copping (1863-1932) was a well-known, successful British illustrator, who is chiefly remembered for his work on illustrated bibles. His career began with work for two magazines which we discussed in relation to John Henry Spencer’s collection of children’s periodicals and annuals, the Girl’s Own Paper and the Boy’s Own Paper. Between 1887 and 1900, Copping produced illustrations for these magazines, both owned by the Religious Tract Society. In 1905, the Society funded a trip to Palestine for Copping to prepare work for an illustrated bible, originally titled The Bible in Modern Art. [1] Copping studied at the Royal Academy and won a Landseer scholarship to study in Paris. He was trained to work from life and en plein air. The opportunity to draw from life in Palestine must have been a truly thrilling prospect.

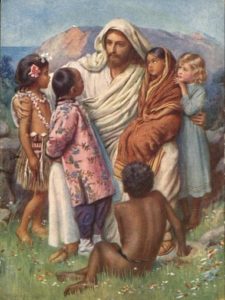

The work, which became known as the ‘Copping Bible’, was published in 1910. It contained 64 coloured illustrations by Copping, the most famous of which was ‘The Hope of the World’.

Harold Copping, The Hope of the World, 1915.

This was Copping’s first commercial success, and many more commissions for similar work came his way. Copping’s illustrations for the ‘Copping’ bible were made into lantern slides and used by British missionaries abroad. The RTS further requested twelve paintings from Copping, three per year at £50 each, for their various publications. If Copping had had the opportunity to derive copyright from his work, he would have been a very rich man indeed. However, in relation to many of his illustrator peers, Copping made a very good living from his work. He was prolific and professional, and contextually uncontroversial.

Today some find Copping’s religious work, especially his missionary subjects, to be uncomfortable viewing. Sandy Brewer has suggested that Copping’s religious work, which has been neglected by art historians, deserves new attention. She argues that in particular Copping’s most famous illustration, The Hope of the World, which shows children from five continents gathered around a benevolent Christ, signifies a shift in the focus of the missionary movement to child centred focus for their projects, and if the ‘imperialistic veneer’ of the painting is lifted that progressive attitudes about ethnicity and gender can be observed. [2]

Our example here from Towneley Hall’s Edwin James Hardcastle collection comes from Copping’s work as an illustrator for a wide variety of secular literary publications. He provided illustrations for Westward Ho!, (1903), Grace Abounding ( 1905), editions of Little Women (1912) and A Christmas Carol ( 1920), as well as many examples of the British public school stories genre, some of which are to be found in the Spencer Collection at the Harris. The illustration featured here is from an unidentified book. If you know it, we would be thrilled to hear from you!

Next time: The Edwin James Hardcastle Collection continued

[1] See Sandy Brewer, ‘Protestant Pedagogy and the Visual Culture of the London Missionary Society’, in Religion, Children’s Literature, and Modernity in Western Europe, 1750-2000, eds Jan de Maeyer, Hans-Heino Ewers and Rita Ghesquière, (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2005), p. 267.

[2] Sandy Brewer, ‘From Darkest England to the Hope of the World: Protestant pedagogy and the visual culture of the London Missionary Society’ in Material Religion; The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief, Volume 1, 2005, Issue 1, pp. 98-124)