Walter Crane, Little Bo Peep

Walter Crane (1845-1915), Little Bo Peep, watercolour and ink on card. On loan from Towneley Hall Museum and Art Gallery.

6 May 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

Walter Crane (1845-1915), like Kate Greenaway and Ralph Caldecott, belonged to the generation of British illustrators who came before most of the largely contemporary artists whom Hardcastle collected. His mature work clearly shows the influence that the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had upon his development as an artist. Crane was a devoted student of John Ruskin, and also a friend of William Morris, whose political views he shared. As well as his innovative work as a designer and illustrator of children’s books, Crane designed images for the British Socialist Movement. Perhaps the greatest influence on his political views however, came from the wood engraver William James Linton, to whom Crane was apprenticed after his father’s death in 1859 when Walter was 14. Linton sounds a very Walt Whitmanesque character, as Crane described him in his autobiography, An Artist’s Reminiscences, published in 1907:

W. J. Linton was in appearance small of stature, but a very remarkable-looking man. His fair hair, rather fine and thin, fell in actual locks to his shoulders, and he wore a long flowing beard and moustache, then beginning to be tinged with grey. A keen, impulsive-looking, highly sensitive face with kindly blue eyes looked out under the unusually broad brim of a black “wideawake.” He wore turn-down collars when the rest of the world mostly turned them up – a loose, continental-looking necktie, black velvet waistcoat, and a long-waisted coat of a very peculiar cut.. [1]

Beyond Linton’s Chartist views, his workshop provided Crane exposure to some of the most innovative artists of the day whose work Linton engraved including Rossetti and Millais. Although Crane’s subsequent work is largely remembered for his innovative approach to children’s book illustration, the influence of the pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts movement, with regard to artistic practice and political views, are clearly present throughout Crane’s personal life and career as an artist. A Masque for the Four Seasons (1905), illustrates the strong influence of the pre-Raphaelites even in the mature work of Crane; the strong use of colour, the heaviness and fall of the draperies and the classical yet medievalised beauty of the personifications of the seasons epitomise the core principles of the movement.

A Masque for the Four Seasons, by Walter Crane, 1905-1909, oil on canvas – Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt – Darmstadt, Germany.

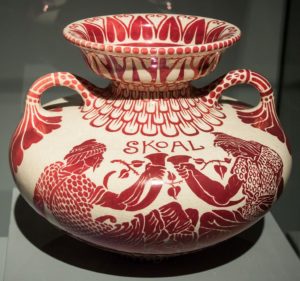

Walter Crane: Skoal – decorative vessel. Manufactured by Maw & Co., Broseley, Benthall Works, Shropshire. Budapest Museum of Applied Arts Collection.

Also through his success as an apprentice of Linton, Crane was introduced to Edmund Evans, who was the leading innovator in colour printing for the new markets opening up for both middle brow and juvenile readers in the last decades of the century. Crane found his metier with his designs for children’s books where his training in wood engraving, his love of rich colour absorbed through the pre-Raphaelites and the technical genius of Evans combined to create some of our most iconic images of children’s illustrations. Crane’s work was tremendously influential on the generation of illustrators who followed him, and his illustrative work is still widely recognised today. Crane did not work exclusively as an illustrator however, but in a wide variety of media. Like his mentor, William Morris, Crane designed for ceramics, textiles and wall paper. The example here from the Budapest Museum, dated 1885, demonstrates the vitality of Crane’s work with its rich colour, striking lines and sense of fun.

Next time: The Edwin James Hardcastle collection continued.

[1] Walter Crane, An Artist’s Reminiscences, (London: Methuen, 1907), p. 57.