Children on a Fence, Kate Greenaway

Kate Greenaway (1846-1901), Children on a Fence, watercolour and ink on paper. Loaned by Towneley Hall Museum and Art Gallery. © Towneley Hall

30 April 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

Kate Greenaway (1846-1901), with her contemporaries Walter Crane and Ralph Caldecott, dominated the world of children’s book illustration for the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Greenaway was a professionally trained artist, and one of the very few women to forge a career as a professional illustrator in the Victorian period. Many facets of Kate Greenaway’s life make her professional success a story of exceptional determination and talent. The Greenaways were a working-class family of four children who lived in Islington where John Greenaway worked as an engraver and his wife, Elizabeth, ran a children’s dress shop. There have been many theories about the genesis of Kate Greenaway’s distinctive and fictive fashions for the children who inhabit her paintings, but to me it seems very likely that her early life spent living over her mother’s fashionable children’s clothing business must have left a deep impression on her artistic sensibilities. Her father’s engraving work, also carried out at home, must have also afforded Kate the opportunity to observe his craft, as well as the engravings he produced for famous artists such as John Leech, who illustrated Dickens’ A Christmas Carol in 1843, and the John Gilbert, perhaps best known for his work on Shakespeare’s Songs and Sonnets, published by Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington in 1862.

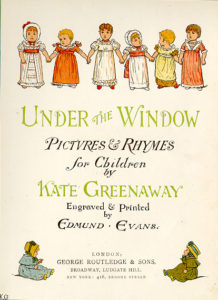

Title page taken from Under the Window: Pictures & Rhymes for Children illustrated by Kate Greenaway, engraved by Edmund Evans, 1879.

Although Kate Greenaway trained at the Royal Female School of Art, the Heatherley School of Fine Art and finally the Slade School of Fine Art, much of her understanding of colour, as well as the process of chromoxylography, she gained through pursuing these subjects herself. She was a frequent visitor to the National Gallery as well as the British Museum, where she studied illuminated medieval manuscripts. Although Greenaway herself perceived insufficiencies in her early technique, her paintings were popular from the start, and she received her first commissions before she had completed her schooling. Greenaway was also fortunate in that her developing style of painting was imminently suitable for the printed greeting card market. As Sonya Rudikoff observed, Greenaway’s fledgling career coincided with the exponential rise of the greeting card market the 1860s. [1] While the production of cards, especially valentines, ensured Greenaway a reliable and comfortable income, she also published illustrated books in her own right, beginning with Under the Window, a collection of poetry for children, in 1879.

Greenaway also found success in the production of bookplates, along with her contemporaries Walter Crane and Aubrey Beardsley. [2]

Birthday Book, 1880 illustration by Kate Greenaway

Even today, Kate Greenaway’s distinctive styling of the clothing for her subjects, particularly for her child subjects, is immediately recognizable. The fictive 18th century attire she developed for her work was nostalgic for her contemporaries, and affects us today in much the same way. What has been lost to us as modern observers of her work is her pursuit of the revolutionary colour printing technique of chromoxylography, where the colours are transferred from hand-engraved wood blocks to the printing surface. For her contemporary audience, Greenaway sought to create the intense colour of medieval illuminations and Netherlandish paintings of the Northern Renaissance. It’s important to contextualise Greenaway within the artistic oevre of her time. Her friendships with Edward Burne-Jones and Walter Crane, and her position firmly at the centre of contemporary design belie our modern perception of her work as perhaps conservative. During her too short life, Kate Greenaway pushed boundaries both in art and life. Her works survives her, as does the Kate Greenaway Medal which has been awarded annually since 1955 by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals.

Next time: Edwin James Hardcastle Collection continued

[1] See Sonya Rudikoff, ‘A Past Recaptured’ in The American Scholar, Vol. 52., no.3, pp. 408-411.

[2] See James Keenan, The Art of the Bookplate, (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2003), pp. 23-24.