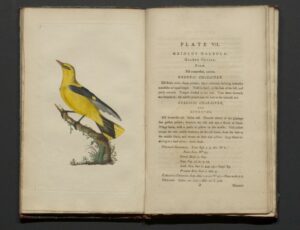

Edward Donovan, The Natural History of British Birds

Edward Donovan, The Natural History of British Birds, London, for the author, (1799-1819), with hand coloured engravings. On loan from Blackburn with Darwen Library and Information Service.

29 May 2020

By Dr Cynthia Johnston, Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

Although Edward Donovan (1768-1837) was one of the best-known naturalists of his time, he rarely travelled out of London. Instead of pursuing his subjects in the field, which ranged from British birds and insects to the insects of China, India, and islands of the Pacific Ocean, Donovan drew from collected specimens. It seems that Donovan curated his own collection of specimens which he studied for his drawings, but he also retained these taxidermy birds, preserved beetles and pressed plants for his own pleasure.

This was not an unusual pursuit for his time, nor indeed into the twentieth century. Blackburn Museum holds the extraordinary Arthur Bowdler coleoptera collection of dried beetles from all over the world. Selections from this collection of over 4000 specimens are on permanent display at the Museum. Bowdler seems to have sorted his storage problems (he ended up with 26 cases of beetles) by donating them to the Museum. Donovan had another approach; in 1807 he opened his own museum, the London Museum and Institute of Natural History on Catherine Street in the Strand. The museum housed hundreds of cases of mostly British flora and fauna all organized according to the Linnaean system; entry for the public was charged at 1 shilling. It was also possible to purchase Donovan’s books at his museum. His multi-volume publications included: The Natural History of British Birds (1792–97), The Natural History of British Insects (1792–1813), The Natural History of British Fishes (1802–08). The museum closed in 1817, and its entire contents were sold at an auction the following year. The auction was reported to have lasted for 8 days.

Pl. 43 of Edward Donovan, Natural history of the insects of China, 1838.

By looking at the examples we have here from James Dunn’s copy of The Natural History of British Birds, it is easy to see the appeal of Donovan’s art, even for the non-specialist. Dunn’s interest in the engraving processes is evident from the large amount of 18th century engraved and printed material in his collection. Most of Dunn’s material is French, so it is interesting to see what appealed to him with regard to British publications. Donovan completed all of the many segments of production which were involved in the publication of his books. He drew the specimens, produced the etchings and engravings, and did much of the hand-colouring himself, although it seems he did have assistants for this part of the process. By virtue of this book being seldom opened since its donation to the Blackburn Library, the colours which Donovan chose to illustrate his subjects are just as vivid for us as they were for his eighteenth and early nineteenth century audiences. The perching bird’s wings flash yellow, and the Chinese moths seem ready to flicker off into the air.